The Kingdom of the Wuffings, the land of the Eastern Angles, appears to correspond more of less to the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. It is a region formed by nature. To the north and east it is given shape by the sea, though the coastline must have changed much down the centuries as the waves have eroded away headlands and silted up estuaries. To the west lie the Fenlands, a vast wetland which, apart from islands like Ely, seem to have been largely uninhabited for many generations after the flooding which followed the end of the Roman period. To the south lay the wildwoods of northern Essex and several rivers running west to east, of which the greatest, the Stour, still marks the southern boundary of Suffolk.

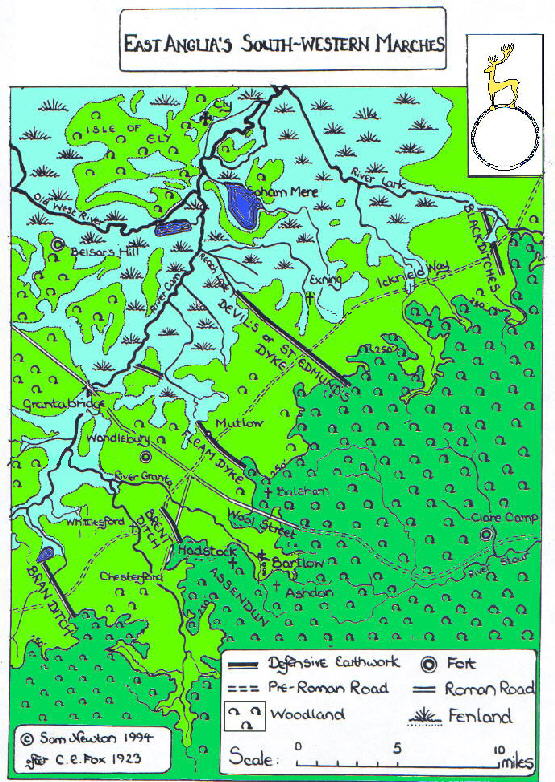

This leaves only one point where there is open land access into the Kingdom – in the south-west, where the ancient roads of the Icknield Way run across the chalk margin between the fenlands of the River Cam and its tributaries and the largely wooded clay uplands of the north-eastern arm of the Chiltern Hills. And it is here that a series of linear earthworks can be seen still standing guard over the kingdom’s south-west approaches.

Dating from the time of the kingdom’s formation during the fifth and sixth centuries, as recent archaeological work has shown, these earthworks form successive defensive lines facing south-west and with their flanks formerly secured by forest and fen. Known as Dykes or Ditches [from the Old English dic], they include Bran [or Heydon] Ditch, Brent Ditch, Fleam Dyke, Devil’s [or St Edmund’s] Dyke, and Black Ditches.

A sketch map of the south-western defence lines of the Wuffing kingdom

The largest are Fleam Dyke and Devil’s Dyke. These Dykes might have formed the main defences that the East Anglian army held against the great raid by the army of Penda of Mercia around the year 640. Bede’s brief account implies that Penda’s advance was initially held long enough to enable the ex-king Sigeberht to be brought to the front line from his minster at Beodericsworth [Bury St Edmund’s] [Historia Ecclesiastica III, 18].

These are probably also the Dykes to which MS A of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle refers in its entry for the year 905. Here we are told that the West Saxon king Edward the Elder pursued his cousin and dynastic rival Æthelwold and his East Anglian allies, led by the Danish king Eohric, as they retreated towards south-west East Anglia after raiding Wessex.

Þa for Eadweard cyning æfter, swa he raðost mehte his fird gegadrian, Then fared Edward king after [them] as soon as he might his force gather, ond oferhergade eall hira land betwuh dicum ond Wusan. and harried over all their land between Dykes & [the Great] Ouse, eall oð ða fennas norð…. (905 MS A [904] ) all as far as the Fens [to the] north…. (my translation)If we take the river named as Wusa to be to the Great Ouse, rather than the Little Ouse or the Wissey, the implication is that the East Anglian army retreated behind the Dykes, beyond which Edward would not follow. Instead, he harried Danish controlled Cambridgeshire from the Dykes to the east and the Great Ouse, near Huntingdon, in the west, and as far north as the southern edge of the Fens. The Battle of the Holm followed, presumably when the Danes counter-attacked. In this battle, the exact site of which is uncertain, both Æthelwold and Eohric were killed.

Devil’s or St Edmund’s Dyke (author’s picture)

It is probably Devil’s Dyke, the greatest of the series, to which Abbo of Fleury refers as a strategic defence line for the kingdom in his Passion of St Edmund, written not far away at Ramsey Abbey in the late nine-eighties. After describing East Anglia’s natural defences of sea, river, and marsh, Abbo says that

on the side where the sun sets, the region is in contact with the rest of the island [of Britain] and on that account accessible; but as a bar to constant invasion by an enemy, a ditch sunk in the earth is fortified by a rampart equivalent to wall of great height (Passio II).

The great linear earthwork named since late medieval times as Devil’s Dyke was formerly known as St Edmund’s Dyke or simply Miceldic, ‘Great Ditch’. Its north-west end meets the Fen edge at Reach, where Reach Lode continues the line out into the Fens. From Reach the Dyke stetches inland for over seven miles, its south-east end being anchored in the wooded uplands near Dullingham. A footpath runs along the top of almost the entire length of its impressive rampart, which in places is still over sixty feet from the bottom of a ditch up to fifteen feet below ground surface. In many places it is astonishingly well preserved, apparently because, as recent work has shown, its builders managed to achieve the perfect angle for its sides so that the weather would cause the least damage.

Looking south-east up the line of Devil’s Dyke towards Gallow’s Hill near Burwell, showing its well-preserved profile on the skyline (author’s photograph)

The 7.5-mile length of Devil’s Dyke is aligned with precise straightness for 5.5 miles with just slight deflections at each end. It differs from other dykes in the series not only in its great length. For some reason, its line does not follow the shortest distance between upland and fen. As Sir Cyril Fox pointed out (The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region [Cambridge 1923], pp.124-125), Reach at its fenward end is on a promontory; an adjacent alignment, e.g. from Dullingham to Swaffham Bulbeck, would have shortened the required line by about two miles.

The great height and length of Devil’s Dyke implies a considerable degree of skill in planning and building. By analogy with the building of the early nineteenth-century railway embankments, it may be estimated that it would have taken around a thousand men about a year to build a single one-mile section.

Looking north-west along towards the fen edge with the Sutton Hoo Society on the march, Autumn 2012 (author’s photograph)

The implication of the building of this major strategic line is that it was a royal undertaking utilising the resources of the whole kingdom. Once completed the Dyke marked the kingdom’s frontier for subsequent generations to see. In times of peace traffic moving up and down the ancient roads in and out of the kingdom would have been manageable by being channeled through gates. In times of war it would have functioned as a shield against enemy forces – certainly Abbo of Fleury regarded it a military deterrent [see the quotation above]. It later centuries it would mark part of the south-west edge of the Liberty of St Edmund and of Suffolk.

Fleam Dyke (author’s photograph)

Fleam Dyke lies some six miles south-west of the Devil’s Dyke. In places its rampart still rises up to about 50 feet from the bottom of a ditch 11 feet, for its builders appear to have achieved the same ideal profile as the Devil’s Dyke. It also seems to be of similar early Anglo-Saxon date.

Part of Fleam Dyke near Mutlow Hill, looking south-east (author’s photograph)

In other respects Fleam Dyke differs from Devil’s Dyke. Its line looks much economically planned than that of the latter and more practical to man. Its fenward end incorporates Fulbourne Fen as part of its defence from where its main section of runs inland in a slightly curving line of around three miles up to something of a headland in the higher ground near Balsham. It also includes in its line a large Bronze Age barrow (dated to c.2000 BC) known as Mutlow Hill, the ‘meeting mound’ for adjacent hundreds in the early medieval period.

Fox thought it likely that Fleam Dyke was in use as a defence line in the context of the great raids on East Anglia by Penda of Mercia around the years 640 and 650 (Archaeology of the Cambridge Region, pp.129-131). The name of the Dyke may also derive from this period, for it seems to be based on the Old English fleama, ‘flight’. Perhaps this was the line from which the East Anglian army retreated to Devil’s Dyke after the initial clash of arms, as Bede may imply in his account of Penda’s raid of c.640 [HE III, 18]. In the ensuing battle the East Anglian army was put to flight despite the presence on the field of the Wuffing priest-king Sigeberht (c.630-640), Rædwa1d’s step-son.

Looking north-west up the line of Fleam Dyke near Mutlow Hill with my Madingley Hall Summer School (author’s photograph, August 2003)

Further Reading

Fox, Sir Cyril, The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region (Cambridge 1923).

Malim, T., K.Penn, B.Robinson, G.Wait, K.Welsh, et al., “New Evidence on the Cambridgeshire Dykes and Worsted Steet Roman Road”, Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society, LXXXV (1996), pp.27-122.

Return to Wuffing Sites Page