The Royal Sword Blade

At the heart of the burial chamber the king’s body had lain. Alongside him, by his right arm, was placed his sword. When it emerged into the light of that summer of 1939 after some 1300 years underground, the sword was rusted and also broken by the fall of the burial chamber roof, but its gold- and gem-adorned hilt fittings and belt mounts sparkled intact.

Its appearance in the soil as it was excavated recalled the following description of the ancient blades from the dragon’s mound in the Old English epic of Beowulf (ll.3048b-3050):

… dyre swyrd,

omige þurhetone, swá hie wið eorðan fæðm

þúsend wintra þær eardodon.

… cherished swords, by rust eaten through, since they in earthern fathom [a] thousand winters there had lain. [my translation]

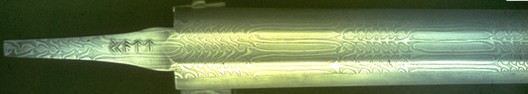

The Mound One sword lies today reassembled in the British Museum. The blade is just under three feet long, and is still sheathed in its wool-lined scabbard of wood, leather and textile. The scabbard has been preserved by the oxides of the rusting blade to which it is now fused into one solid oxidised mass. The blade, however, is visible under X-ray, which reveal it to have been of a very high quality pattern-welded type. It was forged from eight bundles of seven fine iron rods, either twist-forged with alternating twists or left untwisted, all hammered together back to back on an anvil to form the superb blade This means that it was a true weapon, a war-blade, and not just for ceremonial purposes.

It is currently thought that as the Wuffing craftsmen were capable of producing extremely high-quality wrought ironwork, as is shown by the hanging chain for the great cauldron of beaten copper found in the eastern end of the burial chamber, the blade itself may have been forger in East Anglia.

Besides imparting great tensile strength to the blade, the pattern welding process gave it a distinctive rippled interlace appearance when polished, as the splendid British Museum replica shows.

The top half of the replica sword blade in the British Museum, showing the pattern welding as well as the maker’s name (Scott) punched in Old English runic letters on the tang. The lower end of the rusted original can be seen just above it in the background (author’s photograph).

The distinctive surface appearance of the pattern welded replica recalls descriptions of individual sword-blades in Beowulf as brogden-mæl, ‘woven-blade’ or ‘blade with a woven pattern’ (ll.1616, 1667); wunden-mæl, ‘wounden-blade’ or ‘blade with a winding [or coiled] pattern’ (l.1521b); or wæg-sweord, ‘wave-sword’ or ‘sword with a wavy pattern’ (l.1489a).

That the tang of the replica blade is stamped in Old English runic letters with the name of its maker – Scott – gives the replica an authentic touch, for the original could have been similarly inscribed. Makers’ marks or runic signatures on the tangs of blades have been found on sites of formerly sacrificial lakes in southern Scandinavia such as Nydam or Vimose.

It is also possible that original sword itself had a name. Certainly it was the custom in the Old English Northlands to give names to fine swords and other items of personal war-gear. Again, Beowulf provides some good examples. The hero’s own blade is called Nægling. Another famous sword in the epic is called Hrunting, and it is introduced thus (ll.1457-1461):

wæs þæm hæftmece Hrunting nama;

þæt wæs án foran ealdgestreona;

ecg wæs íren, atertánum fáh,

áhyrded heaþoswate; næfre hit æt hilde ne swac

manna ængum þara þe hit mid mundum bewand…

… was the hafted blade Hrunting named; that was [the] foremost of ancient treasures; [its] edge was iron, shining with venom-twigs, hardened in battle-blood; it never failed in the fight any man who grasped it in [his] hand… [my translation]

Hrunting is said to be atertanum fah, ‘shining with venom-twigs [i.e. with tiny serpent-shapes]’ (l.1459b), a phrase which is widely interpreted as referring metaphorically to the distinctive rippled appearance of a polished pattern-welded blade , just as appears on the replica of the Sutton Hoo example.

It is appropriate that the formerly magnificent blade of the original was fitted with a hilt and harness of great richness, the gold and bejewelled mounts of which have survived. The hilt was beautifully adorned with gold, gold-filigree, and gold-cloisonné (in which red garnet gems, and in places blue glass and millefiori, have been set into honeycomb-like structures of gold). It truly was a weapon fit for a king. Let us now look more closely at these mounts.

© Copyright Dr Sam Newton AD 2000, 2014